Framed or unframed, desk size to sofa size, printed by us in Arizona and Alabama since 2007. Explore now.

Shorpy is funded by you. Patreon contributors get an ad-free experience.

Learn more.

- Freeze Frame

- Texas Flyer wanted

- Just a Year Too Soon

- WWII -- Replacing men with women at the railroad crossing.

- Yes, Icing

- You kids drive me nuts!

- NOT An Easy Job

- I wonder

- Just add window boxes

- Icing Platform?

- Indiana Harbor Belt abides

- Freezing haze

- Corrections (for those who care)

- C&NW at Nelson

- Fallen Flags

- A dangerous job made worse

- Water Stop

- Passenger trains have right of way over freights?

- Coal

- Never ceases to amaze me.

- Still chuggin' (in model form)

- Great shot

- Westerly Breeze

- For the men, a trapeze

- Tickled

- Sense of loneliness ...

- 2 cents

- Charm City

- What an Outrage

- Brighton Park

Print Emporium

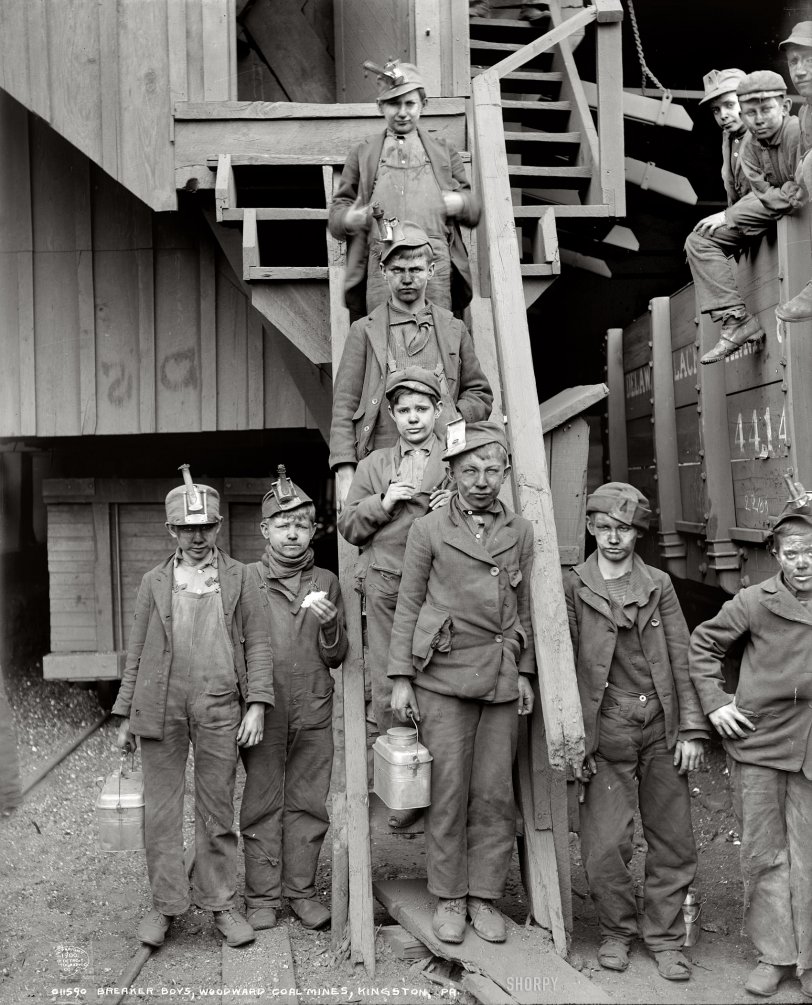

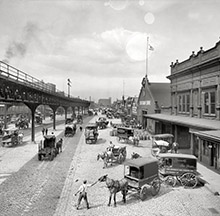

Breaker Boys: 1900

Kingston, Pennsylvania, circa 1900. "Breaker boys, Woodward Coal Mines." 8x10 inch dry plate glass negative, Detroit Publishing Company. View full size.

Well, it happened

We have child labor laws. They grew out of the conditions child laborers faced and are both accepted and preferred in today's economy. Today, our children don't do this. But, at one time, they did. Ample photographic evidence exists of that state of affairs. The child laborers likely did not see themselves as victims, and they are not portrayed as victims in their photos.

How, exactly, should one proceed? Should we not display the photos at all? Should we only display the photos with stern commentary about how awful those days were? Or should we accept the complexity of the situation--that children worked in dangerous and dirty conditions out of both custom and economic necessity, that these children took pride in their work, and that reformers tried to and ultimately succeeded in putting a stop to this labor?

One's perspective.

I think you'll find those who think these boys came out the stronger with no regrets for their child labor are speaking from the position of having done little similar work themselves at any age. Otherwise, you might have a different kind of appreciation for what our forefathers went through growing up in turn of the century USA.

From my perspective, youngsters can always benefit from "work" of some sort but the kind of things documented in these photos only proves how far we've advanced and not how lazy and coddled today's children have become.

My grandpa told stories of waking up in the family log cabin, 5 to 10 years after this photo was taken, and brushing the snow off his bed covers that had blown in overnight. His description of those winter mornings 100 years ago didn't once make me think back on those as the good ol' days, it only made me appreciate modern central heating more.

A great photo

Like Lewis Hine, but with good composition and a budget.

What's for lunch?

Tut tutting and indignation aside, I always wonder what was in their lunch boxes.

My great-granddad

Worked in the Pennsylvania coal mines along with most of his eight brothers, starting at age 15. Grandma said her mother had something like 100 cousins.

Avenging Angels

Always amused by the retroactive righteous indignation so predictably if pointlessly poured out on these pages. The need to tut-tut and show your moral superiority is an itch too powerful not to be scratched in public!

Work Ethic

These young men grew up and gave us the country that we grew up in.

What will we leave behind?

Looking on the brightside

I'm sure slaves likely didn't complain much day to day and made the best of the situation they were in -- would that make slavery an acceptable practice to you?

If Only

If only these young men were able to do some commenting of their own. I imagine they might have a few sharp words for the boo-hoo brigade.

Boggled

I love the photos on this site, but the pervasive idea that child labor was a good thing for those children working long, hard hours in dangerous mines and factories is simply mind-boggling.

Breaker Boys

This is Joe Manning, of the Lewis Hine Project. The previous comments by anonymous are a total misrepresentation of my work and has me more than a bit ticked off. I've posted five stories on my site of boys who worked in coal mines. Only Arthur Albicker was a breaker boy. In 1911, he and another breaker boy fell into an open chute. Arthur was badly injured and the other boy was killed. Arthur eventually recovered and returned to work. He died at the age of 36 from lung disease caused by being gassed in WWI. His wife was pregnant with their first child. Joe Puma was a nipper, later left the mine after he got married, and lived a long life. Vance Palmer was a trapper, but worked in a glass factory almost his whole adult life, and died at the age of 50. Henry Sharp Higginbotham (Shorpy) was a greaser and died in a mining accident at the age of 32, his wife pregnant with their first child. Joe Beafore was photographed by Hine in a glass factory, later worked in the mines, and died at the age of 60. Puma, Palmer, and Beafore were married and had children. Get your facts straight Anonymous, or please don't comment on my work.

Salt of the Earth

I've read enough of Joe Manning's interviews to form a sort of composite biography of these breaker boys, who sorted coal after it came out of the mine. Worked, got married, had four or five kids, lived to a ripe old age. Generally speaking, no regrets.

On Shorpy:

Today’s Top 5