Framed or unframed, desk size to sofa size, printed by us in Arizona and Alabama since 2007. Explore now.

Shorpy is funded by you. Patreon contributors get an ad-free experience.

Learn more.

- Baldwin 62303

- Baldwin VO-1000

- Cold

- No expense spared

- Tough Guys

- Lost in Toyland

- And without gloves

- If I were a blindfolded time traveler

- Smoke Consumer Also Cooks

- Oh that stove!

- Possibly still there?

- What?!?

- $100 Reward

- Freeze Frame

- Texas Flyer wanted

- Just a Year Too Soon

- WWII -- Replacing men with women at the railroad crossing.

- Yes, Icing

- You kids drive me nuts!

- NOT An Easy Job

- I wonder

- Just add window boxes

- Icing Platform?

- Indiana Harbor Belt abides

- Freezing haze

- Corrections (for those who care)

- C&NW at Nelson

- Fallen Flags

- A dangerous job made worse

- Water Stop

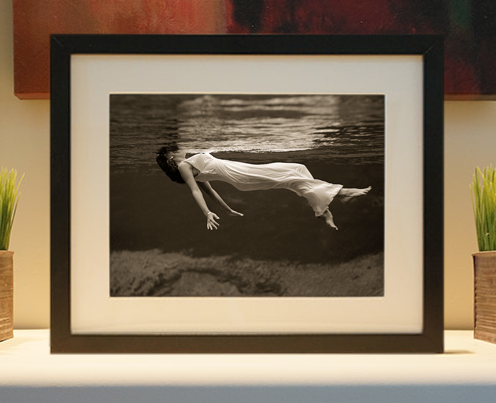

Print Emporium

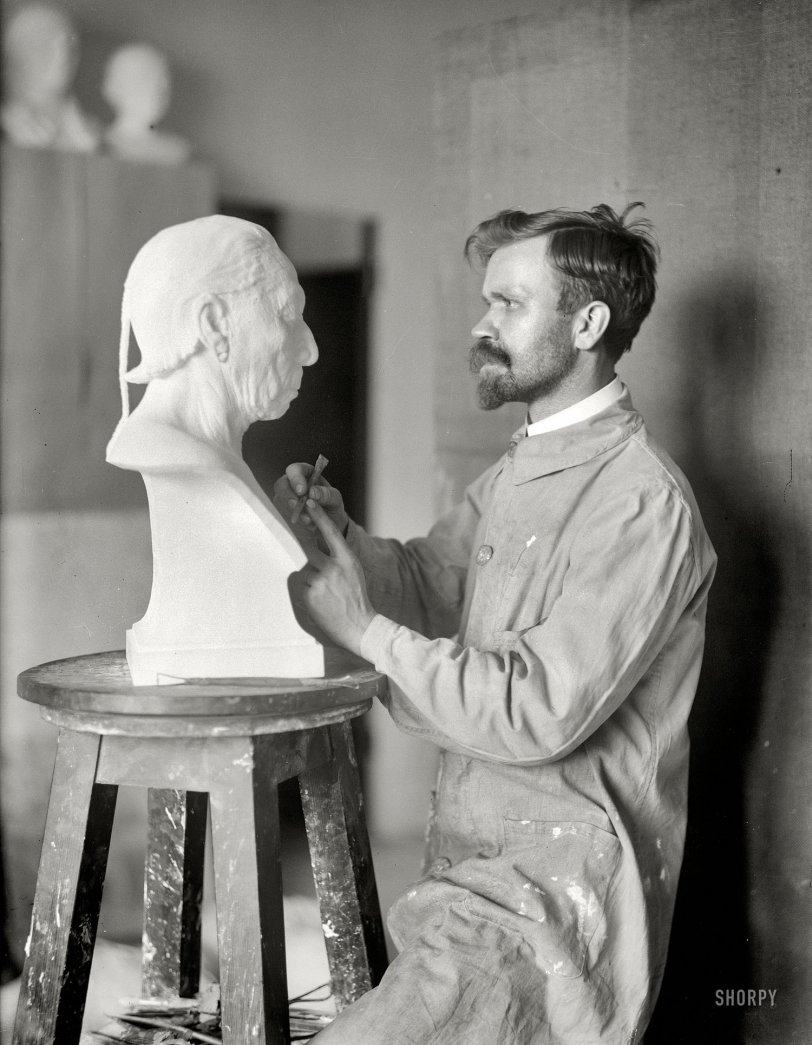

Tete-a-Tete: 1914

Washington, D.C., 1914. "Frank Mischa, sculptor." Co-star in a sort of meta-diorama. Harris & Ewing Collection glass negative. View full size.

Lifecast portrait

The extreme lifelike quality of the skin texture indicates these were almost certainly made by molding directly on the model's skin using plaster or other molding materials. Also the fact that 90 of these finely detailed works were created in short order for an exhibition adds to the likelihood they were cast from life. In lifecasting the front part of the head, including face and neck, are molded, and then the back of the head and hair are recreated, either directly in plaster, or modeled in clay and then the entire composite portrait is molded again and cast in plaster.

Sculpted from life

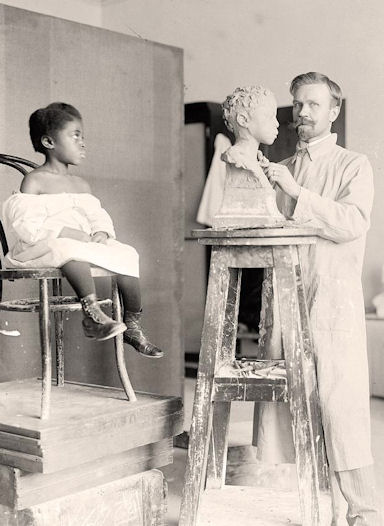

Here's another picture of Frank sculpting an African American child.

Focus --

That's not a staring contest you're ever going to win.

Who blinked first?

My money is on the sculpture.

Frank Micka, Preparator

The artist pictured here was also known as Frank Micka. In 1914 he was an assistant to William H. Egberts, the first exhibitions preparator in the physical anthropology department of the National Museum, as the Smithsonian Institution's Natural History Museum was then called.

The exhibitions department created 90 of these plaster portrait busts of tribal peoples from around the world, for Dr. Ales Hrdlicka's physical anthropology exhibit at the 1915 Panama-California Exposition in San Diego. Titled "The Story of Man through the Ages," and displayed in the "Science of Man" exhibit hall, these hyper-lifelike portrait busts were a tremendous popular success, and helped to build support for the founding in 1917 of the San Diego Museum of Man, now an official affiliate of the Smithsonian Institutions.

In the National Museum's annual report for the year ending June 30, 1914, Micka was credited with finishing and painting the sculptures, and also with fabricating their exhibition cases. Despite his obvious skill and sensitivities, he does not seem to have had any other artistic career, and his name appears in none of the usual indexes of American sculptors.

[The Washington Post refers to him as a "New York sculptor," also as a private in the medical corps of the District National Guard. He is also mentioned a few times (as Frank Mischa) in periodicals of the era. He spent several weeks during the summer of 1912 on the Rosebud Indian reservation in South Dakota looking for models for his marbls busts. Micka and an actor friend, according to the Post, bribed a brave "to visit for several days while he made a study of the characteristics of the young Sioux." - Dave]

Master Plaster Caster

This is how Frank would have made this masterful sculpture:

1. He makes an original from clay.

2. He slops a coat of plaster around the clay to create a mold, using metal strips to create two separate halves.

3. The halves are pried off the clay original and rejoined.

4. Plaster is poured or swirled into the empty mold.

5. The mold is once again removed, leaving a plaster replica of the original clay.

On Shorpy:

Today’s Top 5