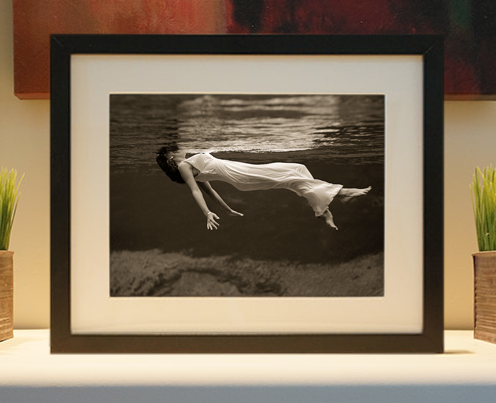

Framed or unframed, desk size to sofa size, printed by us in Arizona and Alabama since 2007. Explore now.

Shorpy is funded by you. Patreon contributors get an ad-free experience.

Learn more.

- Lost in Toyland

- And without gloves

- If I were a blindfolded time traveler

- Smoke Consumer Also Cooks

- Oh that stove!

- Possibly still there?

- What?!?

- $100 Reward

- Freeze Frame

- Texas Flyer wanted

- Just a Year Too Soon

- WWII -- Replacing men with women at the railroad crossing.

- Yes, Icing

- You kids drive me nuts!

- NOT An Easy Job

- I wonder

- Just add window boxes

- Icing Platform?

- Indiana Harbor Belt abides

- Freezing haze

- Corrections (for those who care)

- C&NW at Nelson

- Fallen Flags

- A dangerous job made worse

- Water Stop

- Passenger trains have right of way over freights?

- Coal

- Never ceases to amaze me.

- Still chuggin' (in model form)

- Great shot

Print Emporium

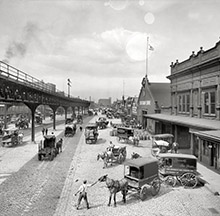

A Fork in the Railroad: 1943

March 1943. "Sumnerfield, Texas. Brakeman running back to his train on the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad between Amarillo, Texas, and Clovis, New Mexico, as it is ready to start again, after having waited in a siding." Photo by Jack Delano for the Office of War Information. View full size.

Spring into action

For those not lucky enough to get a locomotive ride and view a spring frog in action:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oWIB2iF6ld4

Sorry about the shaky video...I only had a few seconds to get the camera up and running. This is video of switching done on the Oregon Pacific Railroad taking a loaded reefer car into the Helico spur in Milwaukie Oregon.

I would have expected that the AT&SF spring frog would have had a larger gap for the main than what is shown to keep wear down. Spring frogs are one of the nicest things to operate over while on the main. My speeder on several runs have ran main-main over these at speed and they are just the smoothest thing. Such a pleasure compared to other regular frogs.

Also, here is a photo from the L.A. area of an old Pacific Electric spring frog where the main line has the wide opening and the siding (to the left) has the closed side of the frog.

Another Delano grand slam

As already pointed out, the switch is definitely a ‘spring switch,’ so designated by the letter “S" on the stand. There are two ways to go through a switch: facing point and trailing point movement. The Delano train had approached the switch as a facing point move, so called because the train faces the switch points as it comes near. Even though the switch is spring loaded, that characteristic is of no benefit to the Delano crew as the switch springs keep the points lined for the main. Hence, the switch must be operated by hand for a route into the siding, and restored for the main by hand once clear. Were Delano headed in the opposite direction, from siding to main, the spring loaded benefit would come into play. Even though the switch is lined for the main, coming out of the siding the wheel flanges compress the point springs such that the switch provides a perfectly safe route to the main. In such a case, the movement constitutes a ‘trailing point’ move. Historically, main line switches were by rule required to be lined for the main once a train was clear of them. Today, in dark track warrant territory a crew can be granted permission to leave a switch ‘wrong’ by checking box 21 on their track warrant. Computer assisted train dispatching will force a line 19 on opposing authority for a different train, requiring it to stop short of the switch before hand operating it.

A further bit of explanation

Our train has "Train Orders" from the dispatcher (or, without specific orders we may just have the timetable showing where opposing scheduled trains are due) and must take this siding get out of the way for the opposing superior train. The engineer of our train and stops just short of the pictured switch o enter the siding.

The front brakeman, also called the "headman", walks ahead of his engine, unlocks the switch ("turnout") to route the train into the siding, gives a hand signal to his engineer to "come ahead", and our train starts slowly ahead. He climbs aboard the engine as it passes by into the siding.

The conductor in the caboose and the rear brakeman, also called "flagman", have copies of the same orders that the engine crew has. From this paperwork the flagman knows that there will be a meet with the opposing train, and that he must restore the switch for the main track to permit the other train to use the main track and proceed forward. The flagman and the conductor go out onto the rear platform of the caboose - the conductor stations himself at the "emergency brake valve" (in case the flagman stumbles) and the flagman stands on the bottom step of the caboose, on the OPPOSITE side of the track from the switchstand. Years of experience has taught him which side of the track every switchstand is located, and he knows that if gets off on the opposite side that he cannot inadvertantly throw the switch ahead of time and accidently derail his own caboose!

The engineer knows exactly how long his train is. He has a list showing him the number of cars in the train and their lengths, and experience has taught him how far it is to every landmark, so he knows not only where his engine is, but also where his caboose is! He slows to a walking speed as the caboose approaches the switch.

As soon as the caboose passes over the switch, the rear brakeman steps across the track, realigns the switch for the main route and locks it. He then runs ahead to catch up to his caboose, and at this moment Mr. Delano immortalized his image on film.

When the engineer nears the other end of the siding, he stops and waits for the opposing train to pass. Then the proceedure is repeated and our train returns onto the main, and our rear brakeman makes another "dash" to catch up with his own caboose on the main track. (Note that on the Santa Fe with flat pair signals he need not realign the switch when it is marked with a letter "S", as in the photo, to indicate that it is a spring switch. The engineer may "run thru" the switch and it will re-align itself.)

Amazing! All done safely without front end/rear end communication, nor communication with the opposing train. Hundreds or thousands of times every day across the continent.

And, the dispatchers communication to our crew telling us all this was expected to happen was as simple as a Train Order stating, "EXA 567 WEST MEET EXA 2651 EAST AT MILBORN". From that simple statement, everyone else knew what his job was.

-LD

Switching switches and fences

The letter "S" on the switch stand probably means "Spring", when a train exits that end of the siding, a Head (front end) Brakeman doesn't have to throw the switch, the train's wheel flanges do the job, and the spring pushes the points back in place.

The extra fence on the left is probably to protect the railroad from wandering cattle on the side road, the field fence only protects from cattle out standing in their field.

The way it looks, now

Google now shows a six lane highway, a large Prairie Skyscraper just off to the right of the siding signals, and the overhead view shows a giant oval of track to service the grain elevator.

Thanks to Delano and Doyle

Another great photo of the plains and trains by Delano and a wonderful explanation by LarryDoyle.

Same as it ever was

I've driven across a good deal of this country over the years, but never have I seen country as open and unobstructed to the horizon as west Texas and eastern New Mexico. You can drive for hours and just not really see anything other than fence posts for as far as the eye can see. I'm willing to bet that this view hasn't changed much in the past 70 years.

Fences

There seems to be one too many fences, if they're to keep cows from straying.

The same field fence ought to serve to protect the road and the tracks.

Excellent clarifications

Jack Delano's caption confused me, too, because of the switch being lined for the main track. The clarifications submitted by swaool and Larry Doyle paint a perfect picture of what is going on.

Another thing that caught my eye is that the caboose is not yet clear of the fouling point, which explains in any case why the brakeman is running.

I'm not a frequent commenter, but I do read what others say. There sure are a lot of knowledgeable people here at Shorpy!

Almost home

I'm a former Easterner, gone native to the desert Southwest thirty-some years ago. Driving I-40 from NC, one is choking with green. In west Texas things fully open up, and you finally see horizon all around. This was once the western edge of Dust Bowl country; to some it still looks desolate, but to me it looks like home is just up the road.

Flat Pair Signals, again

Another exhibit of Santa Fe's Flat Pair signal system: Square blade semaphores with number plates, which every other railroad in North America considered an oxymoron.

See post of 3/20/13, https://www.shorpy.com/node/14899.

Also, note the frog (the point where the two rails intersect) at the bottom edge of the photo does not have flangeways, in either direction. This is a spring loaded frog - each wheel passing through pushes the interfering rail aside.

The brakeman is running, not to get back to his train that has stopped, but rather to catch up to his train that is not going to stop, proceeding slowly away from him. The conductor is likely standing next to the photographer on the rear of the caboose, ready to "pull the air" and stop the train, but only if the brakeman stumbles.

A rare picture of an everyday scene, repeated across the country thousands of times a day, every day, for over a century - Now, seen no more.

Thanks, SHORPY, for posting this gem.

Summerfield

Not Sumnerfield. May be labeled Sumnerfield, but it's actually Summerfield, Castro County, Texas.

The wait is just beginning

More likely that the brakeman (or flagman) has just lined the switch back after his train pulled into the siding. He's running to catch the caboose, as his train will pull down to the other end of the siding to wait for the opposing train, or to be run around by a faster train going the same direction.

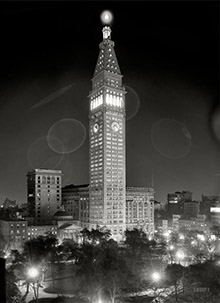

On Shorpy:

Today’s Top 5