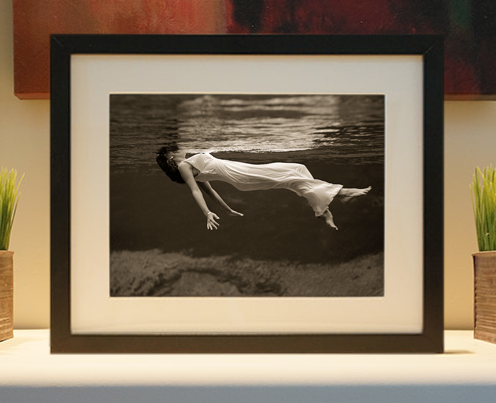

Framed or unframed, desk size to sofa size, printed by us in Arizona and Alabama since 2007. Explore now.

Shorpy is funded by you. Patreon contributors get an ad-free experience.

Learn more.

- Baldwin 62303

- Baldwin VO-1000

- Cold

- No expense spared

- Tough Guys

- Lost in Toyland

- And without gloves

- If I were a blindfolded time traveler

- Smoke Consumer Also Cooks

- Oh that stove!

- Possibly still there?

- What?!?

- $100 Reward

- Freeze Frame

- Texas Flyer wanted

- Just a Year Too Soon

- WWII -- Replacing men with women at the railroad crossing.

- Yes, Icing

- You kids drive me nuts!

- NOT An Easy Job

- I wonder

- Just add window boxes

- Icing Platform?

- Indiana Harbor Belt abides

- Freezing haze

- Corrections (for those who care)

- C&NW at Nelson

- Fallen Flags

- A dangerous job made worse

- Water Stop

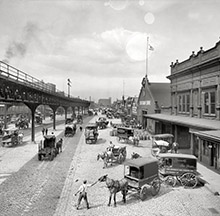

Print Emporium

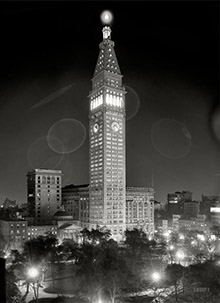

First Across: 1919

100 years ago saw the first trans-Atlantic flight, and it wasn’t Lindbergh’s. A giant Navy seaplane flew from Queens to the Azores in 1919, eight years before the Spirit of St. Louis. It took three weeks. It wasn’t nonstop. — N.Y. Times

May 1919. "The NC-4 Curtiss flying boat, designed by Glenn Curtiss, at Rockaway Beach, Long Island, New York. The NC-4 was the first aircraft to cross the Atlantic Ocean as part of the U.S. Navy transatlantic flight attempt." 5x7 glass negative, Bain News Service. View full size.

Unremarkable

As any school child outside the US knows, British aviators John Alcock and Arthur Brown made the first non-stop transatlantic flight in June 1919. They flew a modified First World War Vickers Vimy bomber from St. John's, Newfoundland, to Clifden, Connemara, County Galway, Ireland. Centennial celebrations are being held in Ireland next month.

There is only ever one first. In this case, crossing the Atlantic by island hopping on a relaxed schedule is not that remarkable.

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Transatlantic_flight_of_Alcock_and_Brown

[Newfoundland (an island!) to Ireland (an island!) is only slightly more impressive than Greenland to Iceland. - Dave]

Hull by Herreshoff

The NC-4 hull was built by the celebrated Herreshoff Manufacturing Co. in Bristol, Rhode Island. There is (or was when I last visited) a superb model of the flying boat in the Herreshoff Museum.

Aviation myths

The vast majority of flying boats (let alone seaplanes) were not designed and built to take down on the open sea. And the vast majority couldn't, accordingly, in anything of a sea swell. The boat part was not risk mitigation, it was the design solution to account for lack of land based infrastructure. As well as saving the weight of a landing gear of limited utility. Plus, Goodyear et al were not quite up yet to making tires that could take the loads associated with (for its time) large aircraft landing gear. After all, we are talking 1919 here. The time when automobiles frequently had two or even more spares, and a full repair kit, and actually needed and used them.

The Spirit of St. Louis used one engine beacause one engine was (barely) enough to get it to Paris. After all, Lindbergh was on a budget. And then as now the engines are easily the most expensive part of an aircraft. And the Wright J-5C Whirlwind was arguably among the most efficient and reliable engines of its time in the first place.

Reliability

Lindbergh chose single engine because he couldn't make it with a failed engine on a multiengined plane anyway. It would just double his chances of not making it to have two engines.

A seaplane isn't out of luck with a failed engine over water.

NC-4 Today in Pensacola

Today's Pensacola New Journal has this article on the NC-4, which is now housed in the Naval Aviation Museum at the Pensacola Naval Air Station.

Pilot was first U.S. Coast Guard airman

He had quite the vision to understand the future of flight in its infancy.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Elmer_Fowler_Stone

Seaplanes for a reason

All early transport planes were seaplanes. The reason is that there were few reliable methods of overland navigation, no airstrips suitable for landing a plane, and no accommodation for either passengers or aircraft inland. Seaports and coastal routes were long established.

These big Navy seaplanes with "Putty" Read & five-man crew did what they could to go from Rockaway Beach - Chatham - Trepassey - Azores - Portugal - France - England. Much of it in bad weather in exposed cockpits.

Flying Boat

Technically, the NC-4 was a flying boat, not a seaplane. Seaplanes were aircraft that could take to the water by having floats fitted in place of wheeled undercarriages.

Three weeks

No wonder it took so long. No Propellers!

On Shorpy:

Today’s Top 5