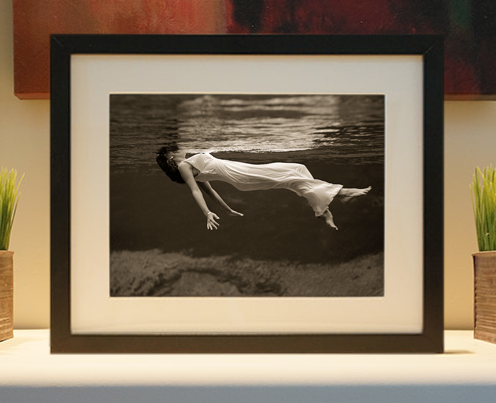

Framed or unframed, desk size to sofa size, printed by us in Arizona and Alabama since 2007. Explore now.

Shorpy is funded by you. Patreon contributors get an ad-free experience.

Learn more.

- Texas Flyer wanted

- Just a Year Too Soon

- WWII -- Replacing men with women at the railroad crossing.

- Yes, Icing

- You kids drive me nuts!

- NOT An Easy Job

- I wonder

- Just add window boxes

- Icing Platform?

- Indiana Harbor Belt abides

- Freezing haze

- Corrections (for those who care)

- C&NW at Nelson

- Fallen Flags

- A dangerous job made worse

- Water Stop

- Passenger trains have right of way over freights?

- Coal

- Never ceases to amaze me.

- Still chuggin' (in model form)

- Great shot

- Westerly Breeze

- For the men, a trapeze

- Tickled

- Sense of loneliness ...

- 2 cents

- Charm City

- What an Outrage

- Brighton Park

- Catenary Supports

Print Emporium

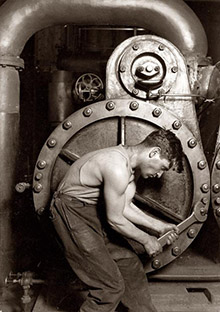

Hammer and Tongs: 1943

March 1943. "Santa Fe R.R. shops, Albuquerque. Hammering out a drawbar on the steam drop hammer in the blacksmith shop." 4x5 Kodachrome transparency by Jack Delano for the Office of War Information. View full size.

DANGEROUS Work

This was Dangerous work, with a capital D.

Nothing like blunt, super-heavy red hot machinery to put human vulnerability into sharp relief. When I see a picture like this I feel a surge of patriotism, despite my cynical metro-self. Dang it, there was a time in this country that when we needed something made or built, we made or built it, right there and then.

[What country is the planet's current No. 1 producer of manufactured goods? It is still the U.S. of A. - Dave]

More Santa Fe railroad shop pictures

Here are some additional pictures of the Santa Fe railroad shops, including several shots of that very same steam hammer and the nearby forge. Other pictures in the series confirm that it is indeed a drawbar being forged. The temperature of steel at orange-yellow is about 1800F. The melting point of steel is around 2500F, depending on the alloy.

The bar and the chain are both steel.

It is certainly possible for the work to head up the chain to glowing, but seeing as both of them are the same material it is impossible for it to melt the chain.

Also they are turning the bar ninety degrees between passes to draw it out square. (Drawing round under flat dies is a bad idea.) Turning the bar brings a different section of the chain in contact with the hot bar. Also the area of contact between the chain and the work is fairly small so the transfer of heat would be slow.

Diesels & Drawbars & Santa Fe

I don't disagree with the discussion on drawbars on diesels, however the shops in Albuquerque were Santa Fe, one of the first railroads to reject the concept of fixed consists in favor of couplers on all units. According to most of the normal sources (McCall's "Early Diesel Daze", for example), this started with the very first road freight locomotive they purchased, FT 100.

It looks to me like they've only just started forging whatever they're making and it's a little too early to say what it's going to be. It could very easily be a side rod or main rod for a steam locomotive.

[We think it's a drawbar because it says so in the caption -- which was written by Jack Delano, who took the picture. - Dave]

Diesels & Drawbars

Actually it wasn't an experiment. Diesels were connected by drawbars for several reasons.

EMD had considerable success with its prewar E units, which carried a pair of prime movers on a single long frame. Railroads liked the concept, but the new, bigger and heavier 567 prime mover designed for the F series freight diesels made this impossible. EMD solved this with the cabless booster, or B unit, which was connected to a standard A unit with a cab. An A-B set is really one locomotive with two prime movers, albeit not under the same body.

Union rules at the time required that each locomotive have an engineer and fireman. So if you wanted to run an A-B + B-A or A+A set of new diesels, you paid two crews. Connecting two, three or four units as one with drawbars (A-A, A-B-A or A-B-B-A) allowed the railroads to circumvent this. And on many railroads, these multi-unit sets all carried the same number, but each had a different letter, such as 1091A, 1091B etc. for the same reason.

The biggest headache was maintenance – if one unit went down, all had to be taken out of service. As diesels took over, the old rules were finally abandoned, and F units were fitted with standard knuckle couplers so they could be mixed and matched as needed.

The Chain

Pretty basic explanation about the chain - if the temperature isn't hot enough to melt the steel drawbar it wouldn't be hot enough to melt the steel chain. In hot working like this, the lower limit in terms of temperature is 2000 degrees Fahrenheit. Melting point of steel varies by the alloy, but it often melts at 2500 degrees Fahrenheit.

One sturdy chain

I admittedly know nothing about metal working but I'm a bit surprised that the big orange glowing bar isn't melting that chain.

Drawbar 101

Drawbars formed a quasi-permanent connecting link between a steam locomotive and its tender. It needed to be physically robust and have exceptionally high tensile (stretching) strength, since it would bear the entire starting/rolling load of a train weighing several thousand tons. The "hammering" you see in the photo was part of the forging process that imbued the drawbar with its strength. Early diesel locomotives experimented with drawbars, but since diesels carried their own fuel, drawbars created an unnecessary limitation to mixing and matching locomotives and were quickly abandoned as a relic of the steam age.

On Shorpy:

Today’s Top 5