Framed or unframed, desk size to sofa size, printed by us in Arizona and Alabama since 2007. Explore now.

Shorpy is funded by you. Patreon contributors get an ad-free experience.

Learn more.

- Lofty addition

- In 1912

- Keenan Building

- Six years old

- Taken from the P.J. McArdle Roadway?

- It stood only 47 years

- Three track mind

- Incline to the right

- Reach for the sky, 1912 style

- No clean sweep

- Same Job Title, Same Face

- Sadly Lost

- Beautiful ...

- Where you get your kicks

- Aim High

- Pueblo Revival sisters

- Pueblo Neoclassicism

- Milk Man

- Regional dialect.

- Spielberg's inspiration

- Great Photo

- Loaf Story

- Do you still have the Rakes category?

- Could almost be a scene from the 1957 movie 'Hell Drivers'

- The Wages of Fear.

- Conspicuous by their absence

- Got Milk?

- All that aluminum

- No lefties

- Smoke 'em if you've got 'em

Print Emporium

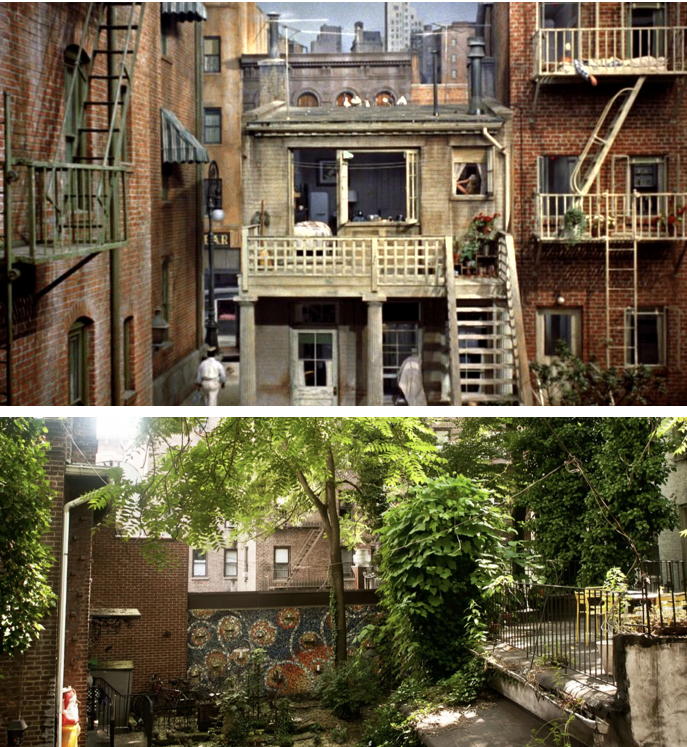

Rear Windows: 1940

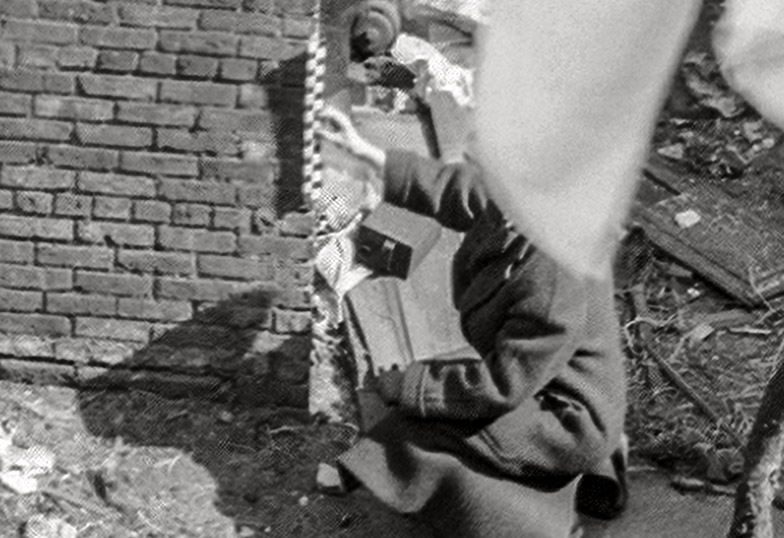

March 22, 1940. New York. "Rear of #68 and #70 Greenwich Street showing dormers and stable ell back of #73 Washington Street at left. Houses built circa 1825." 5x7 inch acetate negative by Stanley P. Mixon for the Historic American Buildings Survey. View full size.

Perspective

These buildings as shown are old and dilapidated to the point of scary moviedom. While never to be confused with The Ritz, these were built to solve a housing problem and offered a tremendous step upward for the original residents. That changes over time, of course.

NY Times on 67 Greenwich

Lengthy and researched NY Times article on 67 Greenwich, a survivor from 1810. Interior completely redone, four floors now three floors, but it is finding new uses today:

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/04/09/realestate/streetscapes-dickey-house-...

Not for long

Actually kinda startling to believe that such tenements still existed in that part of town as late as 1940. But, only 10 years later this entire 2-block stretch would become the entrance/exit to the Battery Park Tunnel to Brooklyn (and a parking garage).

An exceptional resource for exploring NYC during this era:

https://1940s.nyc/

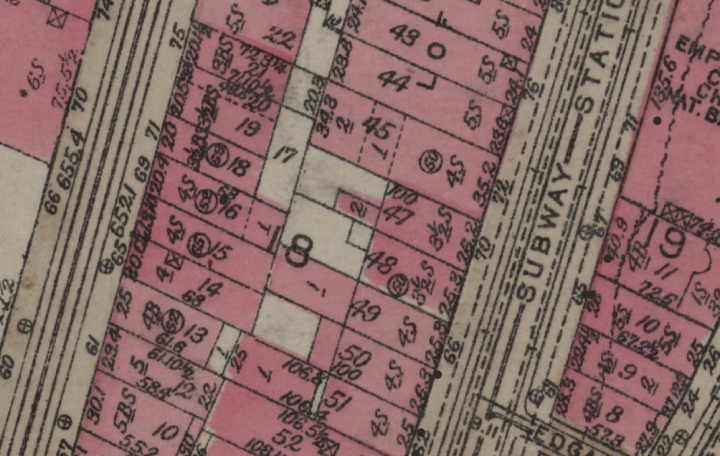

In this view of the map the backyards of the two buildings, and the back structure that our man is surveying, can be clearly seen. This photo would have been shot from the back window of 71 Washington St.

Visible at top center is the Adams Express Building (1914), and to the right of that, the Continental Bank Building (1932).

Looks like fire trap row

Nineteenth-century buildings such as these often shared a common wall between them. The main downtown business street in my community was lined with buildings similar to these, although not so deteriorated back then. Some were wood-frame, others brick. Typically, the buildings had businesses on the first and sometimes second floor, apartments on floors above. In August, 1899, a fire started in one of the downtown buildings. Within hours, the entire core business area was reduced to smoldering ruins.

Common-wall construction facilitated the totality of destruction. Tremendous heat in one building, often on the top or an upper floor, would cause bricks in the common wall to explode, opening the way for fire and smoke to spread into the next building. The brave but overwhelmed firefighters of the time couldn't begin to stop the spread. In the aftermath, the common-wall vulnerability became apparent. City fathers soon passed an ordinance prohibiting that kind of construction, along with other safety requirements.

I'm sure New York City officials knew of the common-wall danger long before 1940. I wonder if these ancient buildings and so many like them were grandfathered in as they were or required to install some sort of add-in firewall.

Not a lot of pulleys

Those laundry lines must have required a lot of effort just to get them to move. Several of them don't seem to be running on pulleys, like the one across the middle of the fram, attaching as a loop in a rope around the top of the chimney. Another, going up to that top window, seems to loop on a hook. I know that this is a "slum" scene, but even for the middle-class, so much work went into something we pretty much take for granted now: laundering clothes.

It's why nearly every person in nearly every old Shorpy photo are wearing soiled, tired, rumpled clothing -- even people of moderate wealth. People looked so different back then, and not just that they were skinny. Their clothes and shoes were not shiny-clean, or fresh and new; their socks were drooping. This, despite the fact that people of the early 20th century generally "dressed-up" in ways that we find astonishing.

So when I see crisp costumes in period-piece movies and television, Shorpy has ruined it for me! I can't make the imaginative leap, because I know that people practically lived in their clothes back then.

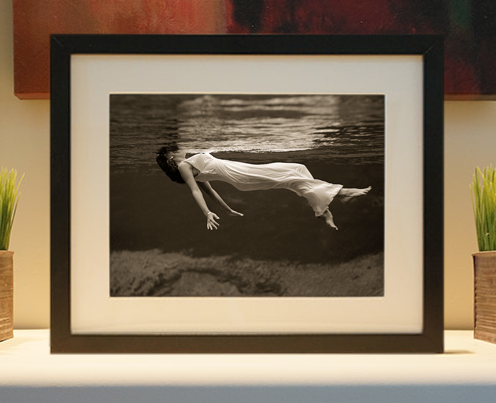

Fictive and real, far and near

The courtyard in Hitchcock's 'Rear Window' was entirely a Hollywood set. (They had to dig out the studio floor, so most of it was below ground level.) However, Hitchcock's designers used an actual location as a reference, the back of 125 Christopher Street. (To complicate matters, the film gives a fictitious address, 125 West Ninth Street, which is not completely fictitious because Christopher Street is what Ninth Street is called west of Sixth Avenue.) That is two miles from Moxon's location; both are 1300 miles from the old Paramount lot.

Put the photos below into black and white, and though more upscale they don't look that different from Moxon's. The Christopher Street courtyard is still intact.

The house across the street survived

67 Greenwich Street, across the street from 68 and 70, is still there. I had to get close; if you back up to get a better view, the address disappears.

Some fingers holding a scale

This person -- presumably a surveyor for HABS -- is much braver than I would have been in standing next to these buildings. They're in pretty bad shape. Greenwich Street, of course, would face another falling wall hazard many years later.

Rear Window.

Hitchcock, of course, made a classic flick of that scene in "Rear Window". Probably one of the greatest films ever made. And Grace Kelly -- sigh.

Problematic

Burglar bars and a fire escape. What could possibly go wrong?

On Shorpy:

Today’s Top 5