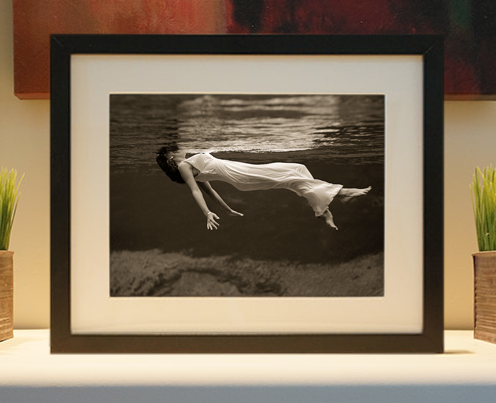

Framed or unframed, desk size to sofa size, printed by us in Arizona and Alabama since 2007. Explore now.

Shorpy is funded by you. Patreon contributors get an ad-free experience.

Learn more.

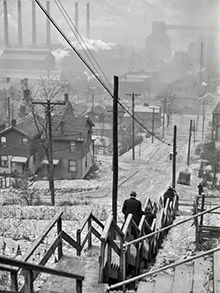

- Lofty addition

- In 1912

- Keenan Building

- Six years old

- Taken from the P.J. McArdle Roadway?

- It stood only 47 years

- Three track mind

- Incline to the right

- Reach for the sky, 1912 style

- No clean sweep

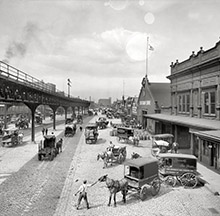

- Same Job Title, Same Face

- Sadly Lost

- Beautiful ...

- Where you get your kicks

- Aim High

- Pueblo Revival sisters

- Pueblo Neoclassicism

- Milk Man

- Regional dialect.

- Spielberg's inspiration

- Great Photo

- Loaf Story

- Do you still have the Rakes category?

- Could almost be a scene from the 1957 movie 'Hell Drivers'

- The Wages of Fear.

- Conspicuous by their absence

- Got Milk?

- All that aluminum

- No lefties

- Smoke 'em if you've got 'em

Print Emporium

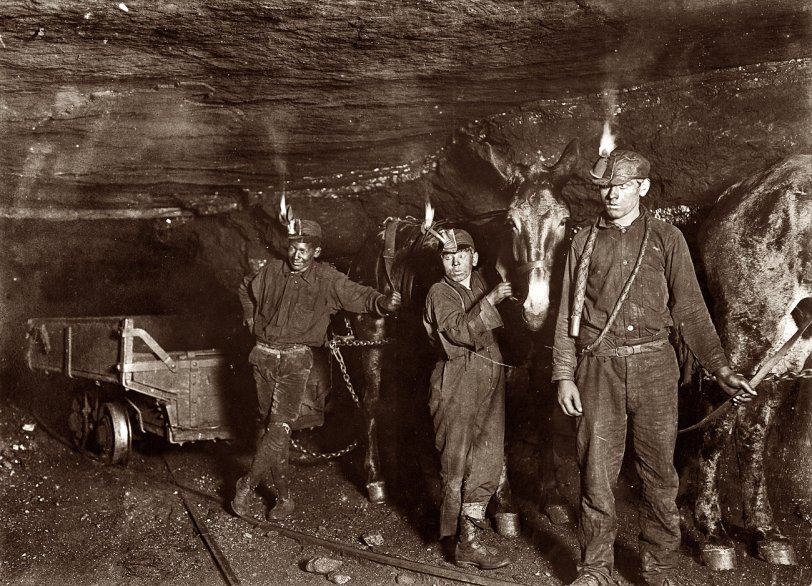

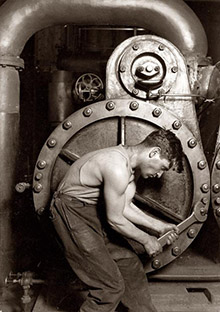

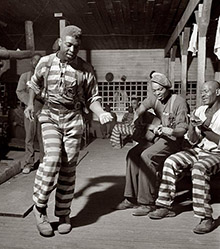

In the Tunnel: 1908

September 1908. Gary, West Virginia. "Drivers and Mules in a coal mine where much of the mining and carrying is done by machinery. Open flame on oil headlamps." View full size.

From the Web site of the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission and the Museum of Anthracite Mining in Ashland:

When men first began to tunnel into the earth to remove coal, open flame lamps or candles were the only devices to light one's way. If a miner opened a pocket of lethal gas, the lack of oxygen could not only snuff out his open flame light — a warning too late — but the lives of miners also could be snuffed out. This is why miners often carried caged live canaries into the tunnels. Canaries are more sensitive than humans to diminished oxygen and poisonous gases and provided an early warning to miners. Even more obvious, an open flame could trigger an explosion or fire. One of the significant collections on display at the Museum of Anthracite Mining is a series of safety lamps. After an explosion in England killed ninety-two miners, a society formed to study and prevent mine explosions approached Sir Humphrey Davy (1778-1829) for his help. In 1816, Davy invented a safety lamp with a wick surrounded by cylindrical netting. The Davy lamp was designed so the flame was quickly extinguished in the presence of dangerous gases, giving the miner enough warning to escape. On the other hand, the lamp did not give off much light and could be extinguished by drafts of harmless air.

A later model that provided brighter light used gasoline instead of oil, but burned hotter, especially in gassy atmospheres, and the glass cylinder that surrounded the light source broke easily from the heat. The light went out frequently, requiring the miner to relight it, risking an explosion. Replacing thick glass with thinner glass helped prevent the lamp from breaking caused by heat expansion, but did nothing, of course, to prevent the lamp from being accidentally dropped or knocked over. The development of the carbide lamp in the 1890s — using as its energy source a combination of calcium carbide and water to produce a jet of acetylene gas lit by a flint sparker — provided bright, easy to ignite lights, but did not solve all safety issues. The U.S. Bureau of Mines reported in 1906 that 53 percent of mine explosions were caused by miners' lamps, and six years later two major mine disasters were attributed to safety lamps.

It was the invention of the battery lamp that revolutionized safe light for miners. Once tungsten replaced carbon filaments, which uses less current, it became possible for portable batteries to be carried by miners. Thomas Edison is lauded for his design in 1913 that provided the miner with a lightweight storage battery, clipped to the trouser belt and connected by a wire to a lamp backed by a parabolic reflector that was fastened to the miner's hat. The wire was locked in place to help prevent a miner from disconnecting it, possibly sparking an explosion.

Matewan, WV

My father was a coal miner in Red Jacket, WV. He got killed in 1955. I was only 2 years of age. There was 18 children in his family that lived in North Matewan.

Ode to the Mule in the Mine

My sweetheart's a mule in the mine.

Way down where the sun never shines.

All day I just sit and I chew and I spit

all over my sweethearts behind.

(This is an old traditional song)

"I'm almost fifteen. There's lots down there younger's me."

Tell it in the country, tell it in the town

Miners down in Mingo laid their shovels down

We won't pull another pillar or load another ton

Or lift another finger till a Union we have won!

Stand up boys, let the bosses know,

Turn your buckets over, turn your candles low.

There's fire in our hearts and fire in our soul

But there ain't gonna be no fire in the hole!

-- Not a real union song: from the movie Matewan. Lyrics by John Sayles.

Workin' in the coal mine, goin' down down

What do you think the odds are all three got black lung?

Exonerated

If you look at the original you can see that he's neither chained to the mule nor the coal car. In the smaller photo it does appear that way, but the chain actually runs behind the boy.

The guy on the left

Is the guy on the left a criminal? He looks to be chained to the mule & coal car.

On Shorpy:

Today’s Top 5