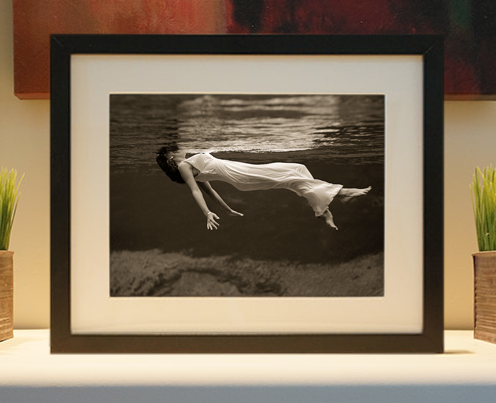

Framed or unframed, desk size to sofa size, printed by us in Arizona and Alabama since 2007. Explore now.

Shorpy is funded by you. Patreon contributors get an ad-free experience.

Learn more.

- Uncle SAAM

- Obfuscation

- One Chocolate Soldier rode away

- Victor Marquis de la Roche

- The Little House Across Way ...

- Vanderbilt Gates

- Vanderbilt Mansion

- You can still see that gate

- Withering heights for me

- So Jim,

- Top Heavy

- Re: Can't Place It.

- Bus ID

- Since you mention it

- The White Pages ?

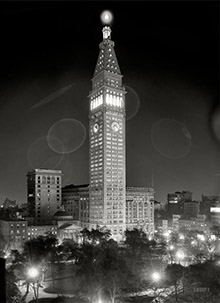

- Moonlight Tower

- 1907?

- Fire(men) and Water

- Can't Place It

- Can anyone

- Wings

- Where's Claudette and Clark?

- Overbuilt Rolodex

- One song

- Give Me Wings Please!

- PRR

- Pinball Wizards

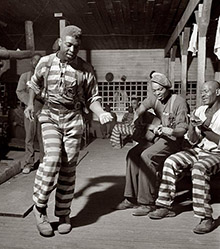

- Possible anti-dancing rationale

- Life imitates art

- Don't dance to the Packard!

Printporium

Carnival Ride From Hell: 1911

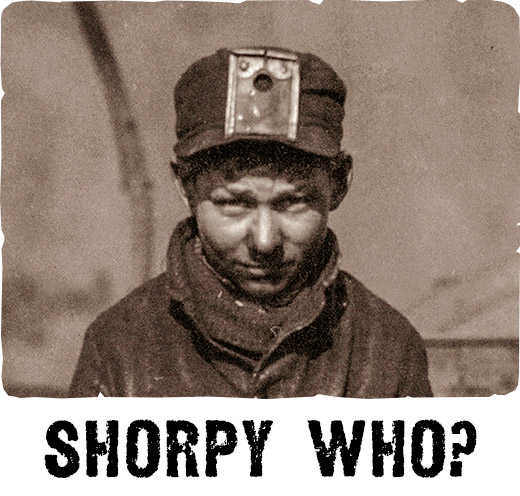

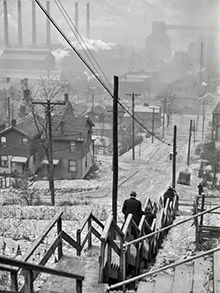

January 1911. South Pittston, Pennsylvania. "A view of the Pennsylvania Breaker. 'Breaker boys' remove rocks and other debris from the coal by hand as it passes beneath them. The dust is so dense at times as to obscure the view and penetrates the utmost recesses of the boys' lungs." Photo by Lewis Wickes Hine. View full size.

From the 1906 book The Bitter Cry of the Children by labor reformer John Spargo:

Work in the coal breakers is exceedingly hard and dangerous. Crouched over the chutes, the boys sit hour after hour, picking out the pieces of slate and other refuse from the coal as it rushes past to the washers. From the cramped position they have to assume, most of them become more or less deformed and bent-backed like old men. When a boy has been working for some time and begins to get round-shouldered, his fellows say that “He’s got his boy to carry round wherever he goes.”

The coal is hard, and accidents to the hands, such as cut, broken, or crushed fingers, are common among the boys. Sometimes there is a worse accident: a terrified shriek is heard, and a boy is mangled and torn in the machinery, or disappears in the chute to be picked out later smothered and dead. Clouds of dust fill the breakers and are inhaled by the boys, laying the foundations for asthma and miners’ consumption.

I once stood in a breaker for half an hour and tried to do the work a 12-year-old boy was doing day after day, for 10 hours at a stretch, for 60 cents a day. The gloom of the breaker appalled me. Outside the sun shone brightly, the air was pellucid, and the birds sang in chorus with the trees and the rivers. Within the breaker there was blackness, clouds of deadly dust enfolded everything, the harsh, grinding roar of the machinery and the ceaseless rushing of coal through the chutes filled the ears. I tried to pick out the pieces of slate from the hurrying stream of coal, often missing them; my hands were bruised and cut in a few minutes; I was covered from head to foot with coal dust, and for many hours afterwards I was expectorating some of the small particles of anthracite I had swallowed.

I could not do that work and live, but there were boys of 10 and 12 years of age doing it for 50 and 60 cents a day. Some of them had never been inside of a school; few of them could read a child’s primer. True, some of them attended the night schools, but after working 10 hours in the breaker the educational results from attending school were practically nil. “We goes fer a good time, an’ we keeps de guys wot’s dere hoppin’ all de time,” said little Owen Jones, whose work I had been trying to do.

From the breakers the boys graduate to the mine depths, where they become door tenders, switch boys, or mule drivers. Here, far below the surface, work is still more dangerous. At 14 or 15 the boys assume the same risks as the men, and are surrounded by the same perils. Nor is it in Pennsylvania only that these conditions exist. In the bituminous mines of West Virginia, boys of 9 or 10 are frequently employed. I met one little fellow 10 years old in Mount Carbon, West Virginia, last year, who was employed as a “trap boy.” Think of what it means to be a trap boy at 10 years of age. It means to sit alone in a dark mine passage hour after hour, with no human soul near; to see no living creature except the mules as they pass with their loads, or a rat or two seeking to share one’s meal; to stand in water or mud that covers the ankles, chilled to the marrow by the cold draughts that rush in when you open the trap door for the mules to pass through; to work for 14 hours — waiting — opening and shutting a door — then waiting again for 60 cents; to reach the surface when all is wrapped in the mantle of night, and to fall to the earth exhausted and have to be carried away to the nearest “shack” to be revived before it is possible to walk to the farther shack called “home.”

Boys 12 years of age may be legally employed in the mines of West Virginia, by day or by night, and for as many hours as the employers care to make them toil or their bodies will stand the strain. Where the disregard of child life is such that this may be done openly and with legal sanction, it is easy to believe what miners have again and again told me — that there are hundreds of little boys of 9 and 10 years of age employed in the coal mines of this state.

-- John Spargo, The Bitter Cry of the Children (New York: Macmillan, 1906)

Gramps Survived This

My granddaddy (1891-1969) was a breaker boy in Pennsylvania. He had to help support a large family. I remember hearing that he got $2 a week and a box of groceries. Then he went off to Europe and fought in WWI in France. He must've been a tough guy but never showed it. He lived a long life but finally black lung disease and a heart attack did him in.

110 years later

This photo is heartbreaking. However, it struck me that today a group of children would have the same posture - all bent over their phones. That is heartbreaking, too, in a different way.

Constant reminder

I live in Northeast Pennsylvania not far from old coal breakers, plus the mountains of culm and coal waste. I was told that the probably the hundreds of thousands tons of this stuff was picked by boys just like these.

Air

I feel honored to join a line of comments that stretches back over 14 years to the time of the original posting of this photo. This is a piteous sight indeed, these children performing appalling work in such cramped and hunched-over positions. The text by Spargo documents the numerous horrible features of the job, not the least of which was the dust in the air. Which makes me wonder: couldn’t the overlords at least have opened that window? Sure, it was January, but wouldn’t the chill have been worth it for the sake of fresh air?

Something to ponder

Behind every "endowment for the arts", "trusts" that built museums and public venues and all originating from the money made in that era there are proverbial hunched shoulders of the boys as on the photo.

From Bad to Worse

Just when I thought Tobacco Tim had it bad, Shorpy's comes up with this. Unfortunately I'm quite sure that things have been even worse for some kids.

What beyond bare subsistence is a livelihood?

Directed to Dave's response to "Mine Owner's Burden":

Perhaps the owners did set foot in the mines, perhaps they did support "the thousands who chose to work there"; but what choice did many of these kids have? Many were either orphaned or born into families without the means to survive if their children did not go to work in the mines. The fact is that the mine owners DID NOT pay a wage that allowed for the families to live above poverty level, even with their sons working beginning work at age 7 or so.

[As Lewis Hine documented in his report to the National Child Labor Committee, hardly any of these children were orphans (back when orphans were usually committed to orphanages). Most of them came from two-parent households that, as Hine took pains to point out, didn't need the extra income. And there were other employment opportunities for boys their age -- work in agriculture, fabric mills, markets, etc. - Dave]

Mine Owners Burden

Do you believe that any of the folks who profited from the work of these children every set foot in one of these mines? Do you believe THEIR children ever had to even lift a finger to get whatever they needed or wanted ? Just the same old story, the elites living on the backs of the majority. Don't think it isn't going on right now, and that it couldn't happen here if the moneyed elite (left and right) could just get their way! Ah, the good old days!

[Yes, they did set foot on the premises. They also provided a livelihood for the thousands of people who chose to work there. - Dave]

Maybe not in America

but people who aren't Americans are still human beings, right? Still people with souls and hearts and, as Neil Gaiman wrote, entire lives inside every one of them.

And we all tend to think of them as lesser beings, or their troubles as less important to us, because they were born on the other side of an artificial border.

Coal Miner's Dollar

This may be a foolish question, but where did the boys put the rocks and debris they retrieved? Was there some kind of separate "trash" channel within the chute? Did they just toss it somewhere to the side?

The text description of the work is chilling. And these children endured this hellhole for less than Loretta Lynn's "miner's dollar" - 60-70 cents a day.

Children staying children....

I remember my US Marine son saying "I'm old enough to vote and to die for my country, but I can't legally drink a beer." He was age 20 when he said this.

Children staying children...

At what age should a child cease to be a child? That's easy. The answer in America is 18. If you're old enough to go to war or vote, you're an adult and it's time to get with it.

I started working part time (with a work permit) at 15, and my father made it clear I had to be self sufficient or in college at 18, after graduating high school. It worked out pretty well, and I think that vast bulk of children today would benefit from a few deadlines.

Children staying children....

Quote "...we are letting children stay children way too long today, ....." Unquote.

Pray tell....at what age should a child cease to be a child?

BK

Canberra

Required School Subject

Perhaps a required course about child labor should be taught in schools. Maybe today's children would gain an appreciation of what they have rather than lamenting what they do not have.

This picture has me wondering..

I realize that children had to work hard to survive back then, but even my generation had to help our parents as soon as we were able to. Aren't we now raising a bunch of lazy kids that will never grow up. First you worked when you turned 6, then 9 or 10. It's getting so that we are letting children stay children way too long today, and parents are spoiling them to the point that often they are still living at home as adults. There has to be a happy medium here somewhere. I expect that in coming years we will still be taking care of our "children" well into their twenties! Don't get me wrong, my heart breaks to see these tiny children in these photos having to do the things they did to survive!

Breaking..

The little boy in the center of the photo looks to be about my son's age. Thinking about my son living that life tears me up. I can't fathom what it would be like to send your child off to that, much less having to work it.

That dangerous line of work made for some amazing photos, and some serious thought...

Think Outside the US

It may not be happening here, in the US of A but that doesn't mean it isn't happening...

A little research

One little search on google answers the question of if this is still allowed to exist.

Breaker Boys

There haven't been any kids in American coal mines since the child labor laws were passed around 80 years ago. Plus of course coal-sorting is automated and done by machines now.

On Shorpy:

Today’s Top 5